Spinning Yarn – Knitting – Meditation – New York Times

Don’t know if this will be accessible after today, so here’s the text:

January 19, 2006

The New Spinners: Yarn Is the Least of It

By ELIZABETH OLSON

THERESE CRUZ is a newcomer to the ancient art of spinning, and she is hooked. She began learning to spin last June, already has two imported wooden spinning wheels and is getting ready to buy an even nicer one.

“It saves me from being addicted to anything else,” Ms. Cruz, 51, said with a laugh as she pressed her bare feet, one after the other, against wooden pedals and steadily fed puffs of colorful fleece into her turning wheel.

She and a dozen other avid spinners had gathered at a fiber workshop in Alexandria, Va., in early January to celebrate St. Distaff’s Day, the ancient English holiday when household chores resumed after the 12 days of Christmas. The spinners had come with their own wheels, from large wooden machines to small Indian charkhas, and were diligently producing yarn thick and thin, colorful and plain, wool and silk.

Spinning, these days often associated with quaint demonstrations by costumed ladies at historic sites like Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, is moving into the mainstream. From knitters who want to take a step back and create their own yarn to those who simply want to be soothed by spinning’s repetitive rhythms, more people are taking it up.

Unlike their colonial counterparts, whose clothing often depended on what was spun at home, many of today’s spinners are not concerned about turning their handiwork into fabric. Nor are they claiming to follow in the footsteps of Mohandas K. Gandhi, who spun every day to persuade Indian villagers to renounce imported textiles and resume making their own cloth.

Many spinners say they have no intention of making anything at all. They churn out skeins of wool, cotton or more exotic fibers like alpaca or camel, and pile up skeins, in their varied colors and textures, for display. Or they give them away to friends and relatives. It is the calming, rhythmic and even meditative effects of spinning that have won many people over.

“It is like taking a trip,” Ms. Cruz said. “It is so tranquilizing to do this at the end of a day.”

Randy Scheessele, 43, who sat beside Ms. Cruz at the gathering, held at the Springwater Fiber Workshop, was making yarn on a drop spindle, an early spinning method that relies on a dowel topped by a hook, a piece of wood or even a CD. “When you come home after a day’s work,” said Mr. Scheessele, an economist at the Department of Housing and Urban Development, “spinning helps you wind down.”

Rain Klepper, a chiropractor and naturopath in Paonia, Colo., who works with cancer patients, said of spinning, “It’s what I call ‘pleasure cruising.’ ” She is so enthusiastic that she now raises her own sheep. “We can all go to Wal-Mart and buy a sweater,” Ms. Klepper, 47, said. “I’m not spinning because I need clothes.”

Many people believe that rhythmic activities help reduce stress and soothe people. “Activities like spinning are meditative,” explained Dr. James S. Gordon, a professor of psychiatry and family medicine at Georgetown University. “You get absorbed in the rhythm, and it is that rhythm and repetitiveness that is relaxing because all the thoughts that crowd the mind can be put aside and the mind is in a neutral state.”

“It is like taking a little vacation from the way our mind works,” added Dr. Gordon, who founded the Center for Mind-Body Medicine in Washington to aid trauma victims.

No one officially tracks the number of spinners, who like weavers and knitters, are not organized. Some, however, connect through Internet spinning sites. Spin-Off, a magazine devoted to spinning, had a 46 percent increase in newsstand sales in the past four years, its publisher reported, and spinning wheel manufacturers have recorded a steady uptick in sales.

“In the past year we have really seen a lift in interest in spinning,” said Marilyn Murphy, president of Interweave Press, which publishes Spin-Off. “Our subscriber numbers are up.” Ms. Murphy said that over the last three years revenue had grown by about 75 percent, not only from the magazine but from sales of how-to books, especially combination titles, pairings of, say, spinning and knitting, or spinning and dyeing.

Sales of Interweave’s spinning book for beginners, “Hands On Spinning” by Lee Raven, have increased by 15 percent in the past five years, she said. In 2000 the quarterly Spin-Off estimated there were 100,000 hand spinners in the United States.

The revival of knitting, said Amy Clarke Moore, the editor of Spin-Off, which is based in Loveland, Colo., has gone hand in hand with spinning as people have become intrigued by luxury and unusual fibers like angora, linen, cotton, cashmere, silk and alpaca.

“We have people who read the magazine who don’t do anything more with what they’ve spun,” Ms. Moore said. “They do it because it is very relaxing to end the day by sitting at their wheel, and they mostly spin for the sake of spinning.”

Spinning’s under-the-radar growth can be found in the details. For example Ms. Cruz, a senior program assistant at the World Bank who lives in Cabin John, Md., said she had to check Web sites vigilantly last year to find an opening in a beginner’s class.

She was introduced to spinning last year at the Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival, a sprawling two-day gathering each May that draws 60,000 people to watch sheep-shearing and herding, to buy bags of fleece and yarn and to choose among hundreds of spinning wheels of every shape, size and price.

“I knew right away I had to learn,” Ms. Cruz recalled.

While fiber arts like spinning were once viewed as hopelessly old-fashioned, they are attracting younger people like Lisa Neel, 26. At a friend’s urging, Ms. Neel started spinning in 2001 while a senior at Yale, astounding her mother, a lawyer in Oklahoma whose idea of Ivy League-educated daughters did not encompass traditional arts like spinning.

Ms. Neel began using a drop spindle, then lucked into a secondhand wheel made by Norman Hall of Oxford, N.Y. Wheels vary in price, but some of the most exquisite are made by craftsmen like Mr. Hall out of woods like cherry and maple. They can cost as much as $5,000. Simpler wheels made out of polyvinyl chloride cost a few hundred dollars.

Now working in McLean, Va., as a project manager at Native American Management Services, which provides services to Indian groups, Ms. Neel spins to relax and gives most of her considerable output to her twin sister, Lara, a photographer in South Dakota who is an expert knitter. Even so, in 2002 Ms. Neel spent about 100 hours spinning yarn for a friend’s wedding chuppa.

When she began spinning four years ago, Ms. Neel said, she felt isolated. But she now frequently taps into blogs to connect with other spinners, who she said are often people with technical backgrounds like nurses and laboratory technicians.

She also cruises the Web to find different types of fleece for her projects. “There were few vendors when I started spinning,” she said, “but there are many more now and it is much easier to find specialized items on the Web.”

Part of the fun is tracking down small sheep farmers like Maureen A. Kane of Barneswallow Farm in Dewittville, N.Y., who breeds Lincoln Crossbred sheep for their shiny, soft and strong fleece, which she sells at festivals.

“I’ve noticed a lot more interest recently, especially in the last four or five years,” Mrs. Kane said. “A lot of it is word of mouth.”

Some who follow spinning say its attraction is part of the nesting trend that followed 9/11 or a second wave of the 1960’s back-to-the-earth movement.

Spinning, Ms. Klepper said, ties its practitioners to long-ago times. She felt those ties deeply after she took up the craft and began raising Icelandic sheep, introduced to Iceland by Vikings in the Middle Ages.

“There is something about reaching back through centuries of time,” Ms. Klepper said. “Knowing that, for example, the Vikings spun fleece from Icelandic sheep for the sail and rope. Of course they used that to go out and pillage.”

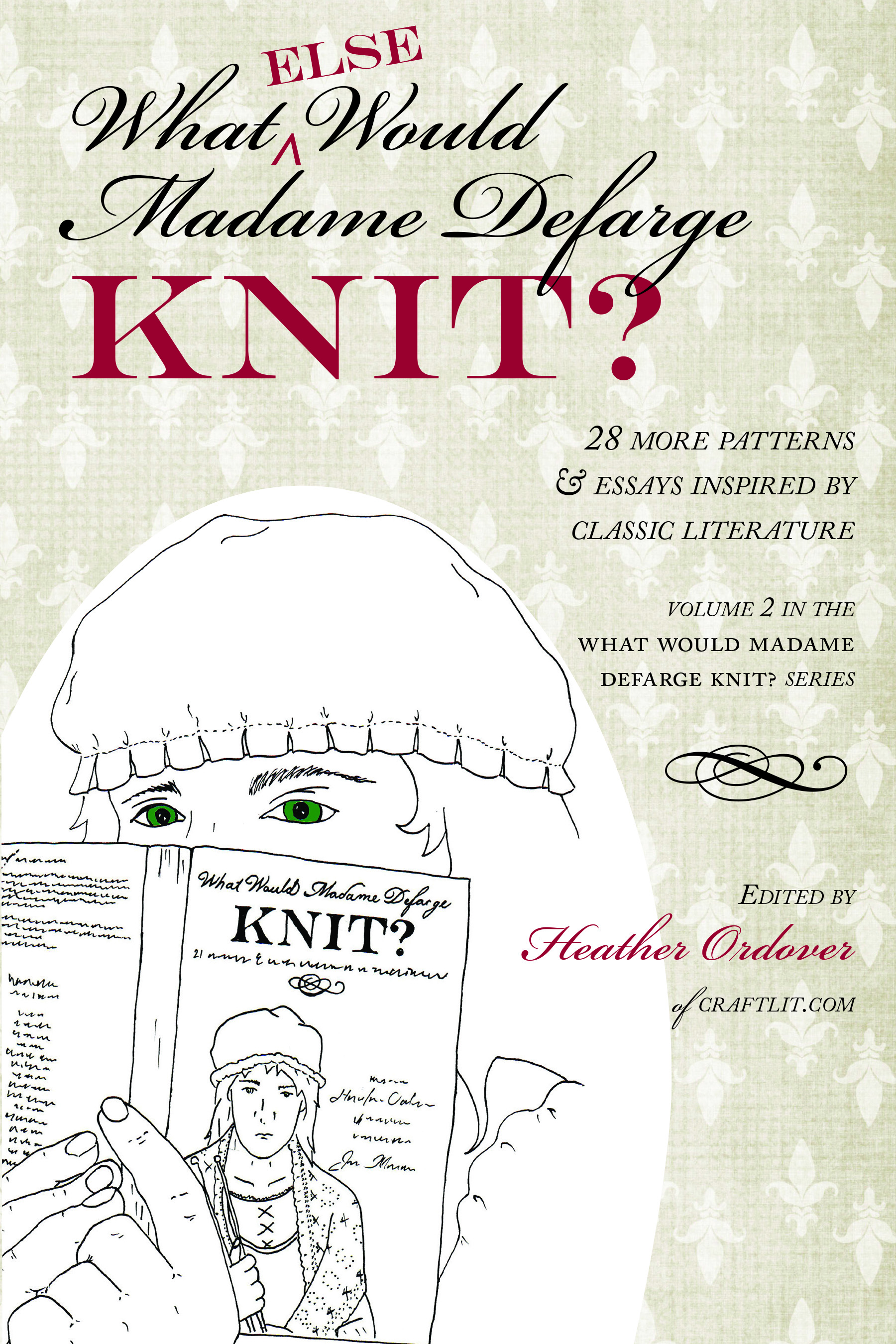

MamaO is Heather Ordover, author, designer, mother and knitter... not necessarily in that order. You can get posts from this blog sent directly to your inbox by signing up below, Follow her on Twitter and Like her on Facebook if you're feeling friendly-like.

MamaO is Heather Ordover, author, designer, mother and knitter... not necessarily in that order. You can get posts from this blog sent directly to your inbox by signing up below, Follow her on Twitter and Like her on Facebook if you're feeling friendly-like.